Shifting Sands – Using Marinas to Drive Ecosystem Health

It was a gift, a stroke of serendipity on a remote beach along Lake Michigan’s Illinois Beach State Park north of metropolitan Chicago. Tantalizingly close to us, amid wind-whipped tall grasses, a stately pair of shoulder-high sandhill cranes strutted in marshy backwaters, clacking loudly as they guarded their nest.

I had stumbled upon the pair with Jenny Bueno, a geospatial technician at the Illinois State Geological Survey. She was preparing to launch a camera drone to survey the state park’s disappearing shoreline.

Relentless currents and storms have been swallowing this coast for years. It is an age-old problem not well solved by the steel shore walls and massive rock barriers, so-called coastal “hardening,” that have been used to date. There is a growing realization that new ideas are needed. The Great Lakes Protection Fund has invested in one promising beacon of hope called Healthy Port Futures that uses submerged, passive landscape architecture to harness natural hydrological forces already in play.

Earlier in the day aboard the state’s specially outfitted coastal mapping vessel, R/V Wabash, Bueno and Chief Scientist Steve Brown from the University of Illinois had shown me a series of aerial photos of the spot where we now stood. In one photo, taken five years earlier, our present location sat inland on a broad chunk of coastal forest and marsh by a road that ran through vegetation to a distant navigation beacon. Each successive photo showed, year by year, how more and more land had been steadily carved away by Lake Michigan’s surf.

“All that land is gone now,” Bueno lamented, “along with the road.” Instead of forest, we walked along a sandy beach amid storm-tossed logs. The navigation beacon where the road had led was a distant point of land separated from us by choppy waters.

With waves crashing nearby, it was clear that in a few years the cranes’ nesting ground would also be gone. But in this little oasis, at this precious moment, tucked away from the waves in a marshy refuge, these regal birds were safe. For now.

“The erosion there is ongoing and dramatic,” Diane Tecic had told me days earlier. As Coastal Management Program Director at the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, her job is to save habitat and wildlife from such threats.

“Every time you come it will look slightly different,” she explained. “It’s that pronounced. We [would] need 80,000 cubic yards of sand at Illinois Beach every year just to maintain status quo. Well, that never happens. We’ve lost acres in the past year.”

Along Lake Michigan’s western shore, with its strong north-south current, headlands and bays that once leapfrogged southward and replenished one another are now vanishing. When people began reinforcing ports and headlands with rock piles and steel walls over a century ago, they broke the natural cycle of migrating shoreline. We humans and our most fragile wildlife have been paying for it ever since with clogged harbors, lost beaches and vanishing habitats.

“Illinois Beach is not very protected,” Tecic added. “We’ve hardened some of it, but it’s probably the most natural shoreline we’ve got, so it’s a sucker for getting hit.”

A few years ago, Tecic started convening local community leaders who had various stretches of lakeshore at risk. Some were losing sand and others had too much. During low lake levels in 2012, sediment carried by residual storms from Hurricane Sandy completely closed Waukegan Harbor, an important industrial port south of Illinois Beach State Park. High lake levels are now just as problematic. Higher water means increased erosion, and recently Lake Michigan nearly equaled the all-time record set in 1986.

As a rule, wherever a stretch of shore is hardened with rock piles or steel walls to prevent erosion, the current along Lake Michigan’s western shore relentlessly chips away at the land directly south. Hardening a coastline is like racing to build ever higher levees along a river’s rising floodwaters, only to worsen floods downstream. Illinois has been running a similar race for generations on Lake Michigan.

Although traditional coastal engineers are working on solutions, they involve large offshore rock structures that are expensive and intrusive. Tecic was looking for an alternative a few years ago when she attended a meeting in Toledo on Great Lakes dredging. By chance, she sat next to Sean Burkholder, a Harvard-trained professor of landscape and urban design now at the University of Pennsylvania.

Burkholder and his colleague Brian Davis, a landscape architecture professor at the University of Virginia, were exploring natural, sustainable solutions to Great Lakes erosion through their Healthy Port Futures work. Tecic and Burkholder discovered they each had something the other needed.

The Healthy Port Futures team had innovative ideas for mitigating erosion and sedimentation at river-mouth harbors, and Tecic already had years of coastal data collection and expertise on how communities interact with shorelines, from industry to recreation. Linking the Burkholder-Davis group with scientists she was already funding at Illinois State Geological Survey and University of Illinois, Tecic put aesthetics on a par with science.

After research and modeling, Healthy Port Futures suggested placing submerged rock blankets on the lakebed where wave energy hits to create drag. The idea was that the hidden structures would do the same job as an obtrusive rock wall for less money, harnessing and amplifying natural forces already at work with fewer unintended consequences such as “downstream” erosion.

“Even if it’s not going to stop everything, it leads us toward a sustainable solution that reduces the amount of sand that has to be placed,” Tecic noted.

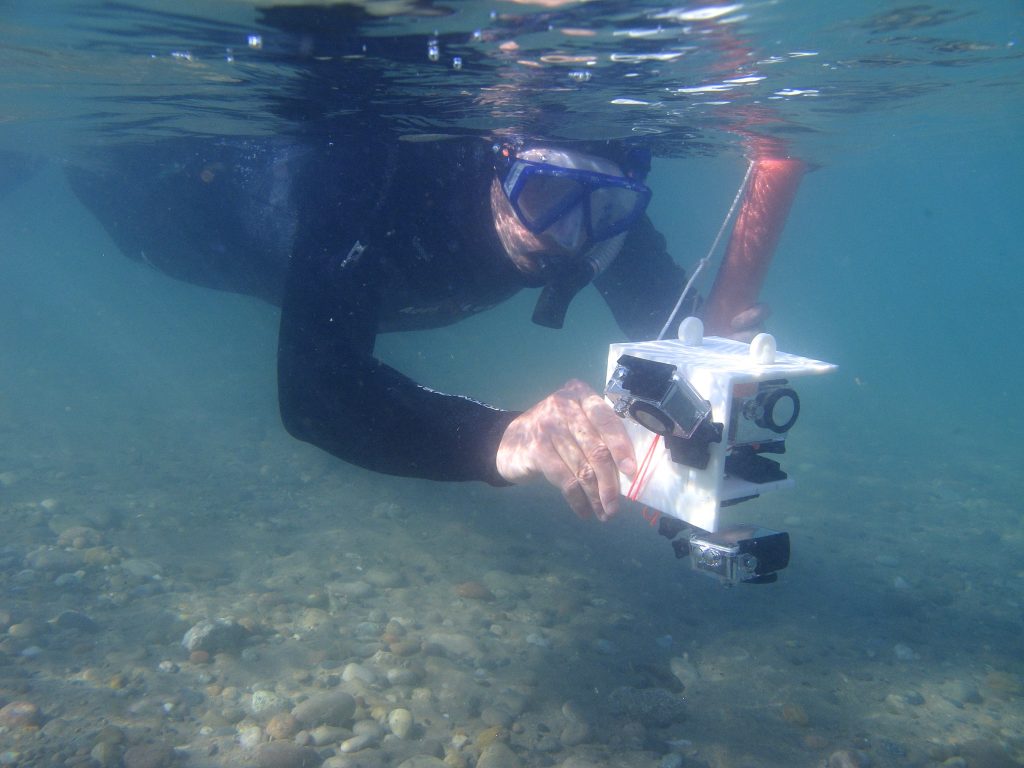

The first challenge was mapping submerged sand bars, past and present, to determine where wave energy was naturally absorbed. Charting a shifting lakebed and all its characteristics such as slope and sediment grain size isn’t easy. It requires drones, boats, sonars, cameras, geologists and snorkelers.

Coastal geologist Ethan Theuerkauf, then at the University of Illinois Chicago, welcomed the challenge. His specialty is geomorphology, with a particular focus on Great Lakes coastal processes and responses—such as how lake levels and storms of varying intensities change shorelines.

The day before I visited with Bueno, Theuerkauf had shown me another shocking example of erosion in the state park. A wooden road barrier with a “Trail Closed for Repair” sign blocked a heavily eroded path that was crumbling into lapping lake waters.

“We’ve been taking bets in my lab group as to when this shoreline would fall in,” he noted. “We were expecting it in July or August, or maybe during the fall storms. But one of our newest lab members who didn’t know as much bet it was going to erode even quicker. He’s winning, so nature has defied us all.”

With a rich library of aerial shoreline photography, shallow-bottom mapping and sediment analysis, Theuerkauf’s colleagues have been vital to the Healthy Port Futures team. A high-tech, wide-beam sonar and other sophisticated equipment aboard the R/V Wabash provides detailed and highly precise charts of the deeper lakebed, overlapping with Theuerkauf’s data in the shallows that border the state park’s most imperiled habitats.

“I have a fundamental science approach, looking at what’s going to happen 10 or 20 years from now, while a typical coastal engineer says, ‘let’s harden the coast and fix this problem now,’” Theuerkauf said. Healthy Port Futures is taking data from the geomorphology group, plugging it into numerical models, and simulating how effective the various submerged lakebed structures will be.

Timing is critical, Theuerkauf believes. Some of the land bordering this rapidly eroding shore is over 1000 years old. What has taken millennia to form is vanishing in a matter of seasons.

Burkholder and Davis are keenly aware that they are in a race against time. They’ve seen what happens when habitat completely disappears. Using Healthy Port Futures funds along Ohio’s industrialized Lake Erie coastline, they plan to reestablish wetlands at river mouth harbors.

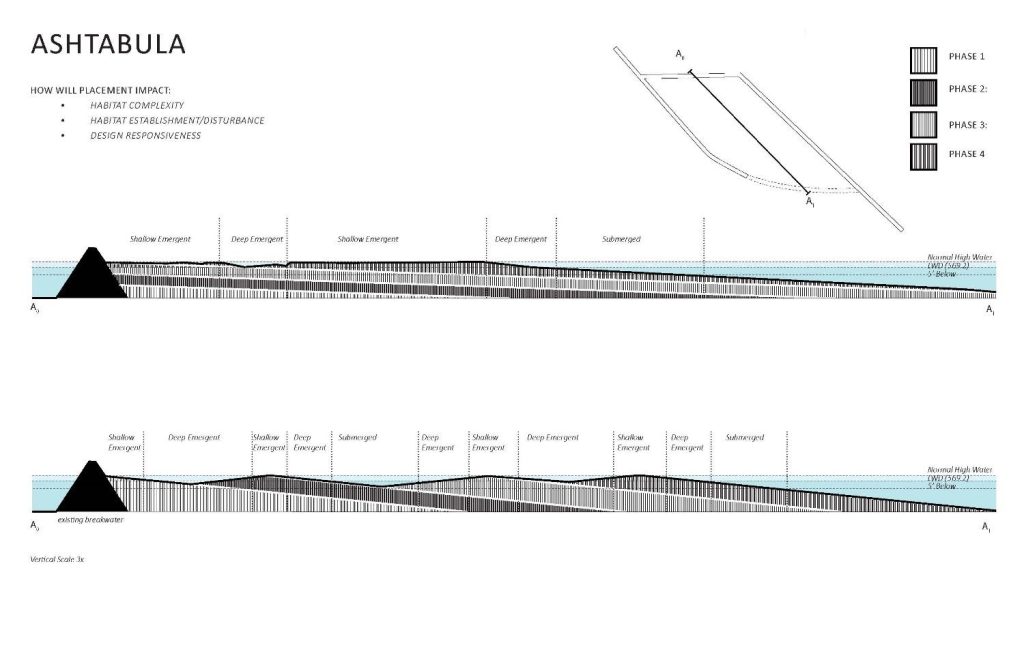

Shipping channels in the economically depressed Lake Erie ports of Ashtabula and Lorain are heavily choked by sediments and must be regularly dredged. It is an expensive enterprise, and that same sediment is needed elsewhere.

Using submerged structures similar to those planned for Illinois Beach, Burkholder and Davis plan to trap sediments where rivers feed the ports, thus creating habitat while precluding the need for dredging. Some visible rock structures may be required to protect the new wetlands from storm action, but actual habitat building will rely on hidden, redirected natural forces.

“It’s not just about creating habitat,” Burkholder noted. “[Our work] is about protecting already endangered habitat. Lake Erie water quality is vastly improved by creating more wetlands, but at this point we can’t even recreate them where they once were because those lands have all been industrialized.”

Healthy Port Futures’ approach of using benign techniques to create aesthetically pleasing coastal landscapes is gaining traction, and it recently won the team a coveted national landscape architecture award. The Army Corps of Engineers’ Buffalo District has already changed its previous port improvement plans to rely less on large rock structures and more on some of the passive approaches proposed by Healthy Port Futures.

“Having a different perspective can be really powerful,” Theuerkauf said as he examined the crumbling foot trail at Illinois Beach. “Yeah, it’s a bit avant-garde to have a couple of landscape architects designing rigorous shore protection and engineering a shoreline, but they’re looking at an age-old problem and trying to combat it with something that’s unique.”

If Healthy Port Futures gets it right by working with nature rather than against it, sandhill cranes at Illinois Beach may still be raising their young for many seasons to come.

Story and photos by Randall Hyman