Vacant to Vibrant: Stormwater Solutions that Fight Urban Blight

- April 29, 2019

When Cleveland’s sludge-clogged Cuyahoga River burst into flames in 1969 for the thirteenth time in a century, it became a rallying cry for America’s fledgling environmental movement.

Now, with the 50th anniversary of that fateful fire fast approaching, places like Cleveland are faced with a more invisible form of water pollution: stormwater runoff, which flushes oil, salt and landscape chemicals from pavements and lawns into our drinking water every time it rains.

In recent decades, cities across the Great Lakes region have been hit with the triple threat of heavier precipitation, aging infrastructure, and weak economies. The infrastructure in many cities needs costly investment and affordable solutions are in high-demand as communities struggle with stagnant economies and slow-growing, or even shrinking, populations. And in Rust Belt cities hard-hit by job loss and foreclosure, abandoned properties blight neighborhoods with tell-tale evidence of decline.

Seeking green solutions

In 2012, three researchers from the Cleveland Botanical Garden drove from Milwaukee to Toronto to see how Great Lakes cities were repurposing vacant lots.

“Around the same time, the EPA and USGS had been studying how small residential vacant lots could absorb stormwater,” recalls Sandra Albro, one of the three researchers, “and they actually found that they absorbed larger quantities of stormwater than expected.”

Taking a cue from those studies and borrowing from their own successes with urban farming in Cleveland, Albro and her colleagues had an idea. In contrast to expensive, large-scale sewer remediation projects, they wondered if the best way to undo urban blight while also reducing stormwater runoff was to unravel it the same way it evolved: lot by lot, block by block. The hope was that small parcels of improvement would inspire locals and spread change from within neighborhoods.

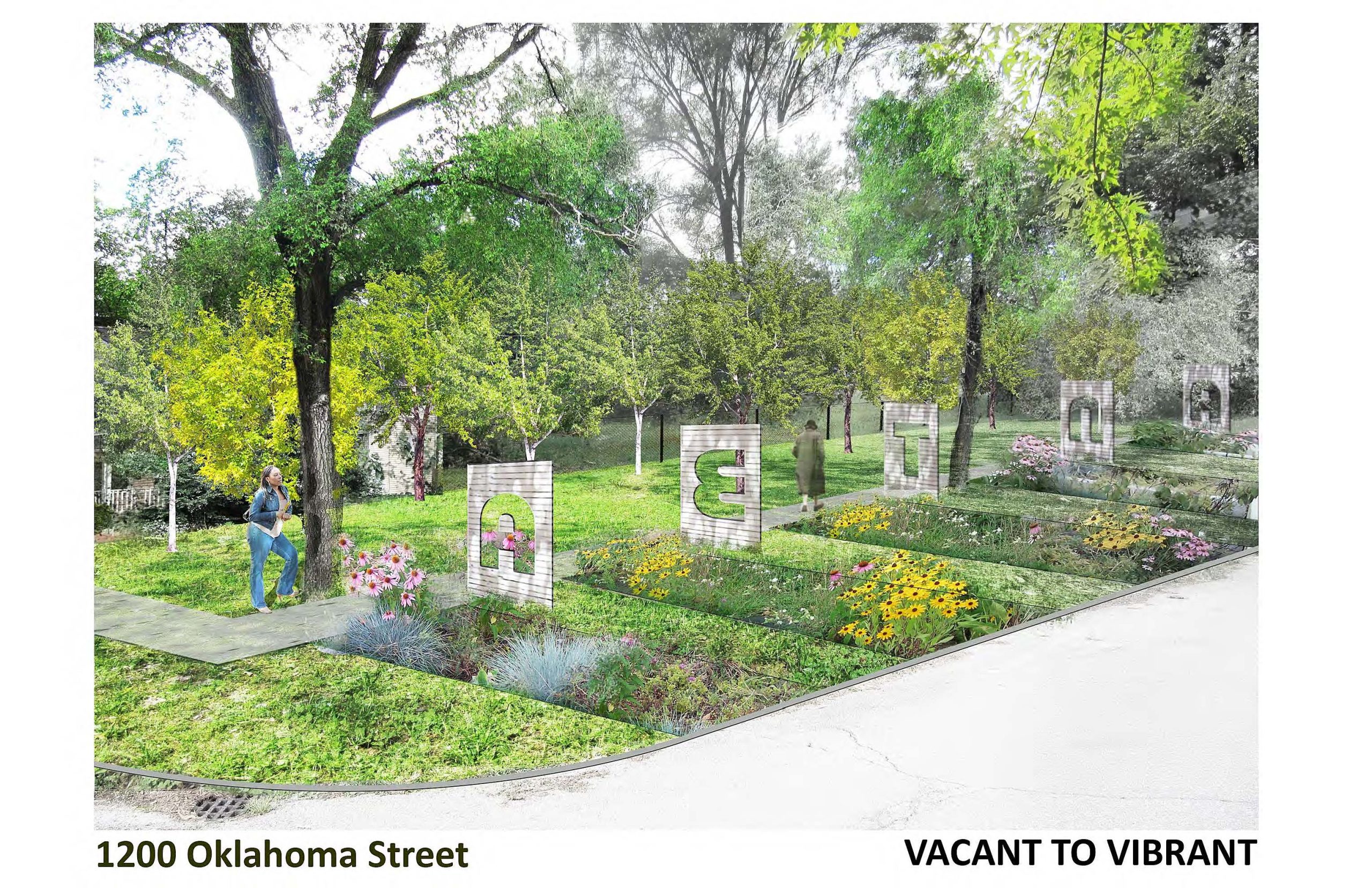

In 2013, with an investment of $902,000 from the Great Lakes Protection Fund to test their strategy, the trio launched the Vacant to Vibrant (V2V) project in Cleveland, Gary and Buffalo, focusing on three test parcels in each city. V2V developed a variety of design solutions with team members that included landscape architects, residents and government officials. They created nine different models for significantly reducing stormwater runoff while tackling urban blight. Designing the lots was the fun part, but understanding neighborhood sensibilities and getting locals to embrace proposed solutions was a challenge.

“In one Cleveland lot,” recalls Albro, who became V2V’s project leader, “we applied some of the same elements we used at the botanical garden to create a children’s nature play area. As soon as it was installed, we started getting complaints from residents. I didn’t understand why till I drove up and saw it with my own eyes.”

In the shuffle of planning, no one anticipated that the landscaped mounds and plastic logs would, in the eyes of locals, replicate typical elements of a vacant lot: dead trees and uneven grading. The site was subsequently redesigned, but enlightening lessons like this were the very point of the V2V pilot sites.

Albro has written a Vacant to Vibrant book on the five-year project which is due out April 30, 2019. It contains a primer of dos and don’ts for urban planners confronted with both tackling urban decay and curbing stormwater runoff. Albro offers her experiences creating infrastructure networks and facilitating more equitable access to green space. Each V2V city yielded valuable takeaways, but Gary, Indiana was a particular success.

Growing green

At first glance, Gary is not a place along the Great Lakes one might turn to for environmental inspiration. Named in 1906 after the founder of U.S. Steel, Elbert Henry Gary, the city is punctuated by aging steel mills and a legacy of water and air pollution.

Within Gary’s 52 square miles – over two Manhattans worth – stand more than 7000 vacant and abandoned properties, among which are one third of its homes.

“We are overwhelmed in terms of managing vacant spaces,” says Brenda Scott-Henry director of Gary’s Environmental Affairs division, “but we can’t give up.”

Working closely with Albro, Scott-Henry has grown fond of the three V2V lots in Aetna, a planned community for steel workers that is now one of Gary’s poorer neighborhoods. She walks amid rain gardens and landscaping swales in a park-like lot on a corner where a burnt-out, two-bedroom home once stood. Five washboards stenciled with the letters A-E-T-N-A stand in a row amid decorative plantings.

“Topography is important,” she says. “You see the slope here? If it rains too much, the water will flow right into that rain garden and stay out of the street. There’s a lot of opportunity associated with these properties.

At each of Aetna’s V2V lots, she looks for any hint of trash or neglected maintenance, but the parcels are neat and clean. Local residents have taken pride in the lots and picked up where the city left off, especially at this grassy corner park.

“A lot of neighbors in this area, they pitch in and cut the grass and keep the weeds pulled,” says Vincent LaRock, a contractor and resident who owns thirteen properties in Aetna.

“They’ve been putting in these gardens and it’s really helped the neighborhood,” he adds. “It’s helped the whole city of Gary actually. They’re on the right track.”

Across Gary, many green infrastructure projects are in place, notably the 30-mile Green Link Trail that will eventually loop around the entire city connecting the Lake Michigan shoreline to the Grand and Little Calumet Rivers.

“We took the best practices from Vacant to Vibrant and we’re applying them to other green infrastructure projects,” says Scott-Henry. “Number one is community engagement. I do not go into a neighborhood where residents are not organized or wanting a difference.”

Sandwiched between steel mills, sand dunes, interstates and Lake Michigan, Gary is a city of contrasts punctuated with surprising oases of beauty. Romantic lagoons and parks from a bygone area have been preserved along with affluent neighborhoods that still line the beach. And in long-neglected neighborhoods like Aetna, where urban renewal has been paired with stormwater control, projects like V2V are spreading hope, parcel by parcel, block by block – and giving cities in the Great Lakes and other regions a road map for fortifying the Clean Water Act in its second half century, city by city.

Story and photos by Randall Hyman.

Cover image of Vacant to Vibrant book courtesy Island Press.