A powerful wave is spreading across the Great Lakes heralding a new age of coastal erosion control. Unlike the relentless surf that gnaws away at vanishing beaches, this is a tide of ideas, a set of natural and affordable alternatives to the obtrusive structures currently girding shorelines.

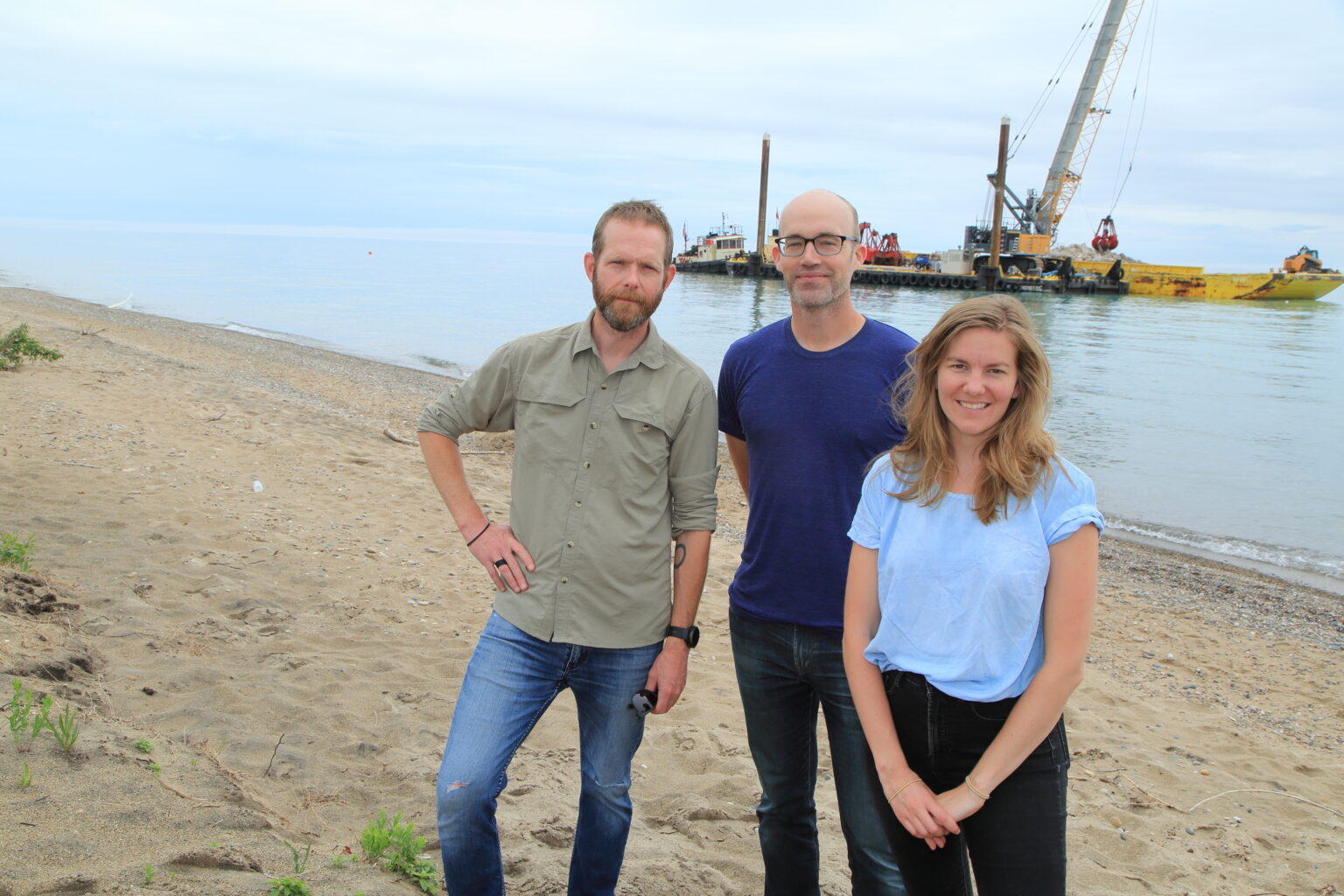

“You shouldn’t have to be Chicago to afford decent coastal protection and landscape creation,” says Brian Davis, Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Virginia. In 2018, with support from the Great Lakes Protection Fund, he and two other landscape architects—Assistant Professor Sean Burkholder and Tess Ruswick of the University of Pennsylvania—launched a project called Healthy Port Futures (HPF) that emphasized form as much as function. It was a radical departure from the heavy-handed engineering solutions that are common across the Great Lakes.

“If you just want to stop waves, you can build something really big that costs a lot of money and forget about it for a while,” says Burkholder. “But we try to educate communities that shoreline protection -could be about doing more than that one thing. It takes time. It’s about investing less money over longer periods rather than lots all at once.”

Two of HPF’s projects, now concluded, enlisted wave power as friend rather than foe. Their research showed how to work with waves by positioning sediment and rocky features in strategic positions to build land where waves and currents were destroying it—all without sacrificing scenic views. The team concentrated on two sites with distinctly different profiles, one on Lake Ontario east of Rochester and the other on Lake Michigan north of Chicago.

The Lake Ontario project at Port Bay, New York involved a critical sand bar protecting homes and a marina. When storm waves breached the bar in 2018, there was extensive economic damage. Rebuilding the natural barrier was costly and ongoing as Lake Ontario water levels continued to fluctuate far beyond historic norms.

The challenge at Illinois Beach State Park was even more daunting. When Lake Michigan water levels peaked in 2019, some eight million pounds of sand were needed annually just to maintain the status quo, a mark that was never met. Though lake levels have since dropped, erosion persists. Recently, the park spent nearly $30 million replenishing its coast with a year-round army of sand-hauling trucks.

Coastal erosion gives as much as it takes, clogging harbors and canals with the very same sediment that it steals from beaches farther “upstream.” Erosion protection in one community can lead to sedimentation problems in another. Communities are forever caught between girding shorelines and dredging harbors, both at great expense.

Rather than simply halting erosion, HPF considered everything from habitat creation to landscape conservation in its planning and designs. One of HPF’s goals was to work with smaller communities to come up with cheaper, better solutions.

Saved by the Bell

At Port Bay, HPF won early converts by saving locals thousands of dollars while turning dredged canal sediment into a valuable resource.

“The end of March is the first time we dredge each year because fishing season opens April 1st,” says Lindsey Gerstenslager, former District Manager of the Wayne County Soil and Water Conservation District.

“When lake levels are low, Port Bay has to dredge every two months, up to five times a season,” she explains.

Before HPF, the small community dredged sediment from its harbor canal and dumped it west of the opening—upcoast and away from the sand bar—where there was a boat ramp and dock. An excavator transferred material to the roadless east side of the canal, but a bulldozer and operator were needed to spread sediment down the bar. The additional equipment and manpower cost an extra $12,000 each time—as much as $60,000 per season.

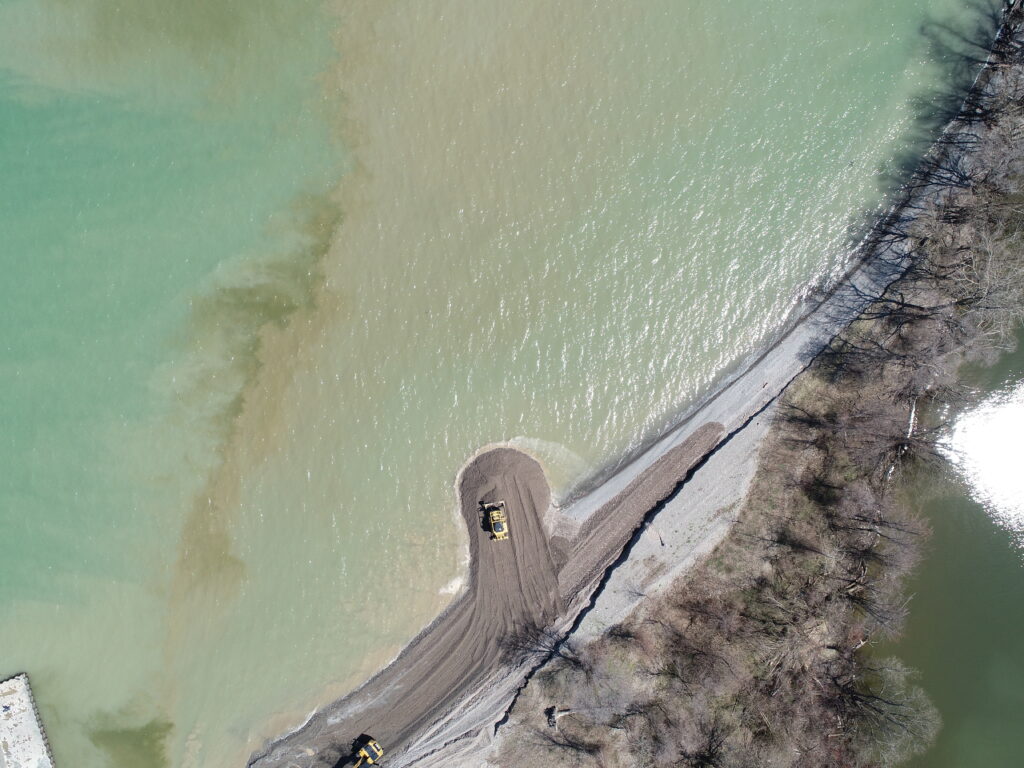

With planning and research from HPF, Port Bay created a semi-permanent feature that Burkholder, Davis, and Ruswick dubbed a “cobble bell,” a tapered feature perpendicular to the beach on the east side of the canal mouth. It was built with sediment dredged from the canal and shaped into a slope that extended out into the lake.

The idea was to let natural wave motion redistribute material along the sand bar without hiring additional earth-moving equipment. They thought the process would take months if it worked at all, but the results were surprising.

From day one, the cobble bell not only sent material along the entire quarter-mile-long sand bar, but did so in a way that placed the coarsest sediment along the weakest points of the reef. It also formed a submerged foundation for future use.

“The first try, it took less than 48 hours for all the material to move and be transferred,” says Gerstenslager, one of HPF’s biggest fans.

“Out of 800 cubic yards of material placed on the cobble bell, we were able to account for over 780 cubic yards that went directly to the shoreline where we hoped it would go. We only lost 20 cubic yards out to the lake.”

While the sand bar has grown, so have the problems that threaten it.

“For 60 years we had consistent water levels. Our levels only went up and down a few inches a season,” explains Gerstenslager. “Now we go up and down feet because the natural swing of things is more erratic.”

Dams on tributary rivers and the St. Lawrence Seaway have altered natural lake flow while climate change has increased swings in precipitation. Erosion and flooding are the result, sending storm waves crashing over the barrier bar during high water and clogging the harbor canal with sediment during low water.

Higher lake levels also transport more sediment. At Port Bay, this feeds an unusual submarine ridge a mere 400 feet offshore along the Rochester Basin where Lake Ontario suddenly plunges to a depth of 800 feet. During lower lake levels and weaker wave movement, the ridge migrates closer to shore. With increasingly dramatic fluctuations in levels, this creates unpredictable navigation.

“You see new high areas that people have been boating on for years where they’re running ashore,” says Gerstenslager.

Incidents like these were another reason she and the Port Bay community joined forces with Davis, Burkholder, and Ruswick. Urgent needs and limited resources made Port Bay a prime candidate for HPF help. Whether the cobble bell is the prime driver of the sand bar’s recovery or lower lake levels are also at play is still unclear, but locals are grateful.

“Every time we’re out there, I see the same people who tell me how the bar is doing and how it’s different or wider than before,” says Ruswick.

“They’re on the ground monitoring, and they see the bar every single day. Those qualitative reports are very useful.”

To assess the cobble bell’s actual impact, the Great Lakes Protection Fund has committed additional funding toward five years of scientific monitoring. The initial results have been promising enough that nearby communities have reached out to Gerstenslager about adopting the practice for their beaches and channels.

Building Land Invisibly

While Port Bay focuses on a single sand bar, Illinois Beach State Park maintains over six miles of shoreline. This narrow, ever-vanishing strip of beach acts as a protective barrier for a millennia-old network of dunes, wetlands, and black oak savanna. Much of that network has become imminently threatened by erosion and flooding over the past few decades.

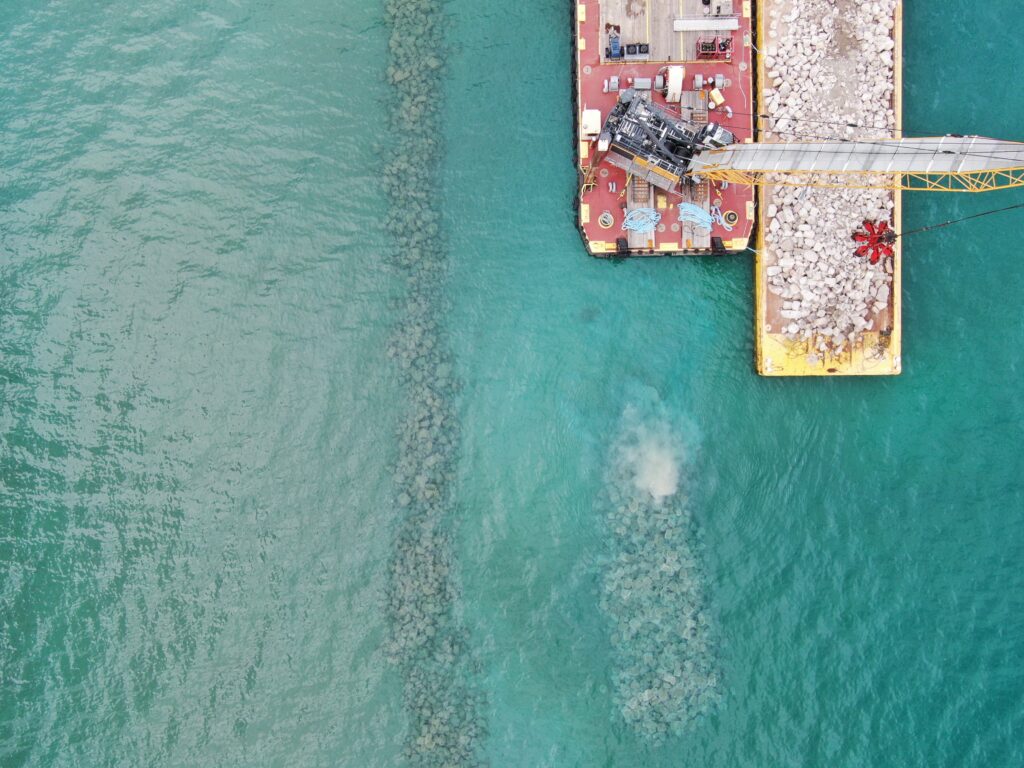

After extensive research and laboratory modeling of the park’s shoreline, HPF suggested placing submerged rock blankets—what the team called “rubble ridges”—on the lakebed to create drag where wave energy hits. The structures aim to work in tandem to harness and amplify natural forces already at work with fewer unintended consequences such as “downstream” erosion. In 2021, a series of three ridges were installed offshore toward the south end of the park.

According to Ania Bayers, a manager with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, this was a new twist to coastal conservation.

“The revolutionary part of their thinking was how to protect the environment while making sure that the experience people get coming to this park wouldn’t be impacted by infrastructure,” she says.

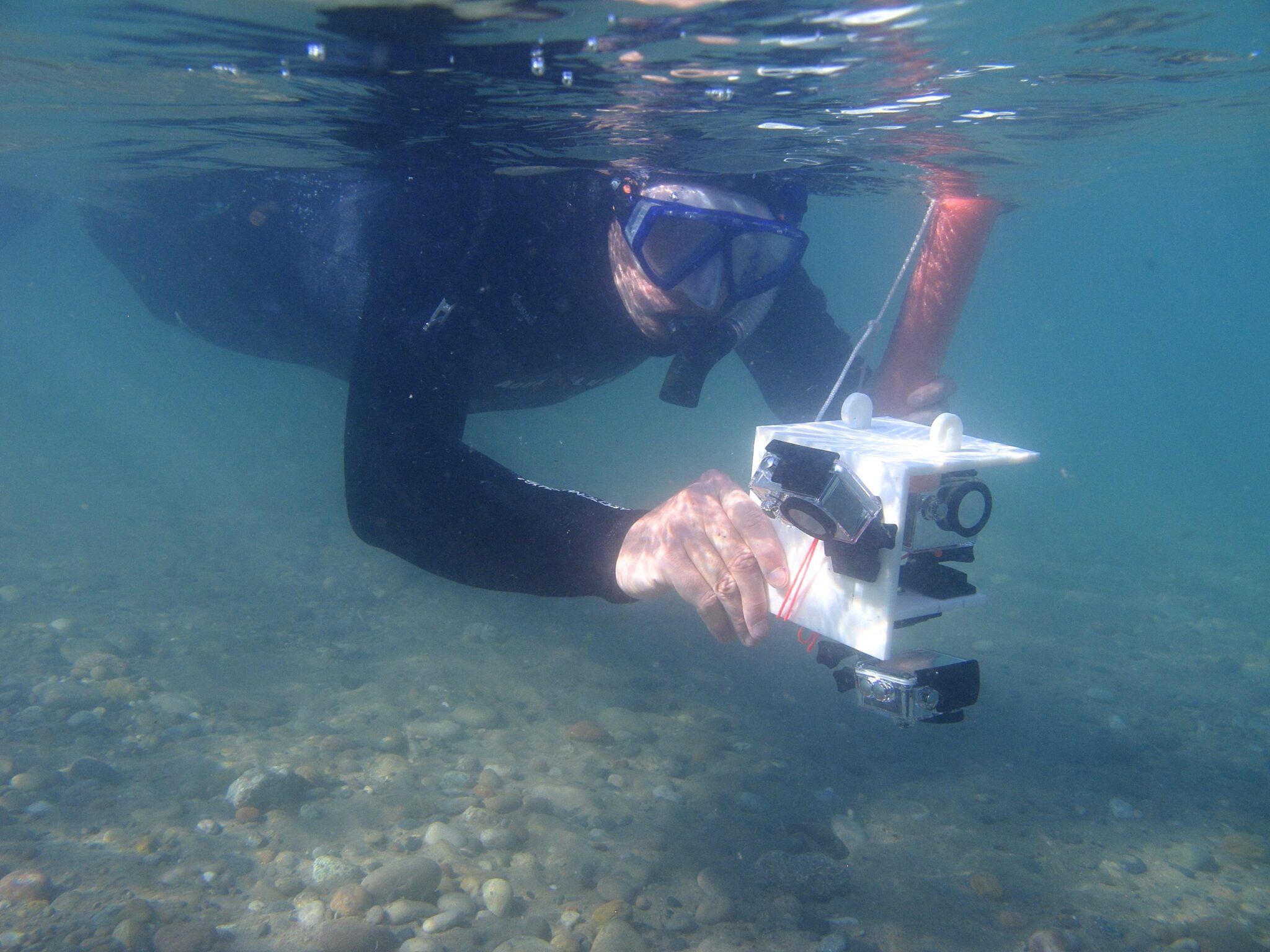

In the four years since the 750-foot-long ridges were installed, lake levels have dropped three feet, making it difficult to know how much of the emerging shoreline is due to the rubble ridges and how much is due to lower water. Drone photos and submarine monitoring have shown a definite improvement, but erosion has continued elsewhere, especially north of the installation.

With that in mind, the park launched an aggressive erosion control program two years ago north of the HPF site. More than two miles of offshore dikes now jut above the lake surface, well within visitors’ view, protecting the massive investment of sand recently hauled onto the beach. Visibility aside, the dikes – designed to mimic natural islands – seem inspired by HPF’s design concepts.

Engineers across the Great Lakes are already taking their cue from HPF’s innovative approaches to curbing coastal erosion.

“Healthy Port Futures was a pioneer,” says Cody Eskew, Coastal Specialist with Illinois Department of Natural Resources. “I’ve been on so many calls with partners, including other state coastal programs and federal agencies like the Army Corps, and they all reference this project.

“Two important lessons that have come out of this are an emphasis away from capital projects as single shot solutions and an emphasis away from very expensive consulting and modeling,” says Davis.

He encapsulates their philosophy with the term “adaptive management,” the idea of tweaking local practices with inexpensive monitoring to preserve natural processes as well as local economies and cultural values.

As the tide of innovation rises, Davis, Burkholder, and Ruswick are still leading the way. They have launched a private consulting firm called Proof Projects, with Ruswick as managing principal, that is servicing communities across the Great Lakes with the mission of bringing affordable coastal conservation solutions to small communities while preserving lakescapes.

Buoyed by funding from the Great Lakes Protection Fund to develop new monitoring technology, Proof Projects is working with engineers to devise drone systems for rapid assessments of local conditions without massive investments in studies. They hope to guide communities toward small tweaks in practices rather than massive overhauls of systems.

With word of HPF’s prowess reaching distant shores, Burkholder says that Proof Projects has been inundated by calls from agencies and consultants wanting them to “do Illinois Beach” elsewhere, from Lake Superior to Lake Okeechobee.

“We tell them it doesn’t work like that,” he says. “It takes a lot of research to figure out what’s going on in a particular place. Those rubble ridges at Illinois Beach are basically the ridges from that landscape, just stretched out into the water—inspired by that landscape.”

The same might be said of the Healthy Port Futures team, inspired by landscape throughout its pioneering work.

For more information on Healthy Port Futures Projects, please visit https://healthyportfutures.com/projects/

Story and photos by Randall Hyman except where noted