Reduced by 90% New Introductions of Invasive Species

Past, Present and Future: The Global Growth of Ballast Water Technology

- By Bob Dolgan

It might come as a surprise to anyone who’s walked a Great Lakes beach laden with invasive zebra and quagga mussel shells, but the two species aren’t particularly common in their home range of the Black and Caspian seas. The invasive mussels have proliferated here because there simply are no species like them in the Great Lakes.

Dan Egan writes in 2017’s Death and Life of the Great Lakes, 27 new exotic species were found in the lakes from 1990 through 2008. Early investments made by the Great Lakes Protection Fund have reduced that invasion rate dramatically and launched an industry aimed at protecting the integrity of the Great Lakes ecosystem.

Past

The Great Lakes have suffered from aquatic invasive species for decades, and now nearly 190 aquatic invasive species have established breeding populations. Trillions of zebra and quagga mussels have perhaps altered the lakes more dramatically than any other invasive.

“Any time you introduce new life to an ecological system, it’s a big deal,”

“I can give you examples of species that are endangered in their home range but invasive outside of it,” says Anthony Ricciardi, a professor who studies invasion ecology and aquatic ecosystems at McGill University. “When you introduce something where there is no native counterpart, that’s when there’s the biggest impact.”

A scientist found the first zebra mussel in Lake St. Clair in 1988, a year before the governors created the Fund. By 1990, scientists had found zebra mussels in all five Great Lakes. Most of the focus at the time was on controlling the invasions of non-native species rather than preventing them.

Faced with a problem and no end in sight, the Fund changed the paradigm to focus on preventing new invasions through ballast water on ships, the primary invasion vector.

“One of the things that was intriguing to us at the Fund was, ‘why,’” said Rankin, who has been at the Fund since the 1990s. “Why was there activity in the solution space, and why were we so clustered in damage documentation? We were looking for opportunities where there was nobody else playing and that was stopping invasions.”

The Fund’s market-driven approach sought to develop and demonstrate ballast water treatment technology—to establish an undeniable precedent. Its ultimate purpose was to create solutions that the industry could use and risk managers could incentivize, and to expand policy makers’ options.

A Series of Firsts

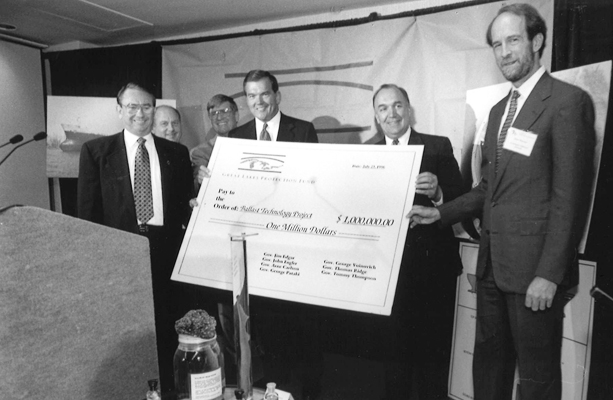

In the late 1990s, the Fund invested $1 million in a team led by the Northeast-Midwest Institute (Washington, DC) and The Lake Carriers’ Association (Cleveland, OH) to demonstrate filtration technology on the Algonorth, a working vessel that transported grain and iron ore. Hyde Products Inc. (Cleveland, OH) assembled the first experimental filtration module.

The success of this early demonstration depended upon an unlikely collaboration among representatives of industry, the Coast Guard, federal agencies, the Canadian government, academics and many more. This diverse collaboration made powerful progress.

“We thought we would put $1 million up for the first team to put together a credible plan for a working unit on a working ship in a year,” Rankin said.

“They got it running with Hyde and other folks, and within a year they could remove 85 to 90% of the organisms that can be a threat.”

As the onboard demonstrations continued, the first International Ballast Technology Investment Fair was convened in Chicago in September 2001. It attracted entrepreneurs, shipping industry leaders, and venture capitalists and proved to be the next logical step in catalyzing the ballast water industry.

“It was one thing to show it could be done [in a pilot project] and another thing to get the industry started,” said Allegra Cangelosi, who led the ballast water team while with Northeast-Midwest Institute. “It was an opportunity to hear directly from ship owners and get investors aware of the need for a new industry.”

Present

According to U.S. and Canadian officials, no unmanaged ballast water has entered the Great Lakes since 2009. In subsequent years, the question facing regulators and advocates was, “How clean is clean ballast water?” The Fund continued to invest in evaluation methods and detection technologies to keep new organisms out of the lakes.

The methods developed in the Great Lakes have become the standard for the entire world. The $17.4 billion ballast water treatment market now includes 22 vendors in 11 countries around the globe. It affects more than 30,000 ships worldwide from cruise boats to fishing vessels to tug and barge units.

“We changed the conversation from documenting problems to creating solutions. In 2006, a new invader arrived every six weeks or so. Now it’s years between new invasion discoveries.” David Rankin, Great Lakes Protection Fund

“The [ballast water industry] is a game-changer,” said Cangelosi. “We didn’t have to fight about whether or not a treatment system might do the job; we could just find out. To have a funder devoted to getting to answers that would otherwise be the subject of endless debate is important to the region and the Great Lakes.”

Future

“You never know when synergistic explosions will occur,” said McGill’s Ricciardi. “All you know is that the more invaders you add, the more they will interact with each other. We stand to benefit by reducing the rate of invasion, but we can aim for zero.”

Reductions in invasion rates are encouraging, but there is still work to do. The Fund will continue to focus on monitoring aquatic invasive species and anticipating the next threat.

“The Fund’s early investments in ballast water technology and further investments in controlling other vectors have decreased the rate of new invasions,” said Steve Cole, the Fund’s vice president of programs. “While this success is encouraging, we will continue to pursue innovations in surveillance tools and control activities.”

—

Start a Conversation

At the Fund, our goal is to build something—together—that delivers impact. You have an idea and a strategy in mind and we have a basin-wide perspective and experience launching new initiatives. We strongly encourage you to contact us to discuss an idea, whether fully formed or not, as a first step.

Email us at startaconversation@glpf.org