The Power of Perception: Culture Change in Farming

Troubled waters

The signs on the sandy beach at Lake Erie’s Maumee Bay State Park offer visitors a dubious welcome: “Have fun on the water… Be alert! Avoid water that: looks like spilled paint… has surface scums… has green globs floating below the surface.” And then the punchline: “Avoid swallowing lake water.”

It is hard on this cold winter day outside Toledo to imagine throngs of bathers flocking here on a scorching July weekend amid such warnings. Equally hard is grasping the connection between the silt-laden floodwaters lapping at my feet and the blue-green algae that bloom each summer like spilled paint across miles of lake waters – resulting a few years ago in a two-day “do not drink” advisory for more than 400,000 people around Toledo.

Lake Erie has made an impressive comeback since the 1960s when some parts were declared dead from industrial pollutants. Now agriculture, not industry, threatens its shores. Northern Ohio is carpeted with farms. Rains, like the one-hour, four-inch downpour that pounded neighboring Seneca County a few days earlier, flush a flood of agricultural silt and fertilizer into rivers feeding the lake. While phosphorous-packed fertilizer fortifies crops, it also bolsters massive blooms of blue-green algae that are toxic to many forms of life, including humans.

Eleven million people, from Toledo to Cleveland to Buffalo, depend on Lake Erie for their drinking water, and the lake supports rich wildlife. Nearly half of the Great Lakes’ fish population resides in its waters, from endangered 300-pound sturgeon scouring its relatively shallow bottom to commercial species like walleye and yellow perch. Fragile birdlife covets the lake’s margins, some nesting, others on critical migratory stopovers. Agricultural chemicals are a major threat to this ecosystem, but there is hope.

Embracing change

Across America, a new generation of farmers is cultivating change to improve water quality with something called cover crops. It is a simple innovation that tucks farmland under a protective blanket of crops all winter ensuring a living root system year-round that binds soils, reduces erosion and invasive weeds, and retains and generates nutrients. It also saves farmers money in the long run by requiring less fertilizer and herbicides.

“Our county does things a little differently,” says Beth Diesch, team leader at Seneca Conservation District. “We’re the only conservation district in Ohio without ‘soil and water’ in our name. It was kind of a branding decision. We’re innovators here.”

Although soil and water are still the agency’s focus, their overriding mission is conservation. That’s one reason Ryan Stockwell, director of National Wildlife Federation’s Sustainable Agriculture program, contacted Diesch a few years ago to enlist her aid in understanding what makes farmers tick. She is an expert communicator and has helped make Seneca County a cover-crop superstar, with some 20% of its land under year-round cultivation versus less than 10% across the Midwest and Great Lakes.

“A lot of field agents see their job as rule enforcers,” says Diesch, a farmer herself. “They’ve got to understand, we’re talking cultural change here, not just rules and pocket books.”

Stockwell is a farmer, too, and as team leader of the Great Lakes Protection Fund grant that is fueling National Wildlife’s cover crop study, he is keen on figuring out how to bring others on board. Many younger farmers now learn about cover crops in college while their parents often learn from experts like Diesch. The vast majority of older farmers, though, reject the concept, citing the extra time, money and risk.

“When I see a bare field with nothing on it in the middle of winter,” says Stockwell, “it’s like a kick in the gut. A lot of us were brought up with the idea that a well-run farm should have neat, tilled fields of straight furrows. We associated that with work accomplished, but didn’t understand the negative consequences of doing things that way.”

Taking a scientific approach to understanding his fellow farmers, Stockwell enlisted Robyn Wilson, a professor in Risk Analysis and Decision Science at The Ohio State University. Wilson grew up on a farm, but her original passion was wildlife. As an undergrad she wrote a thesis on deer management in urban areas that led to an interest in the role of humans in environmental problem solving.

“We keep thinking that if we understand a system better and provide people with information about what solutions might be effective, they’ll just magically get on board,” says Wilson. “It’s pretty clear that’s not the case.”

In 2016, Wilson began talking with Great Lakes soil conservationists to develop a framework for the costs, benefits and risks of cover crops. Next, her team interviewed and surveyed farmers to explore how they talk about it among themselves. Her team discovered information gaps between conservationists and farmers and identified four critical tools for more effective outreach.

First, the study concluded, outreach should be designed to fit individual farmers’ personalities and farm specifics. Next, offer farmers cost-sharing programs that mitigate risk. Third, encourage farmer-to-farmer mentoring in which experienced neighbors provide reassurance and advice. And, finally, emphasize long-term soil health over short-term economic returns.

Providing cover

Wilson’s research breaks farmers into three basic groups ranging from avid proponents to hesitant candidates. Brian Snavely, of southeast Seneca County, is fully sold on cover crops but not yet fully invested across his entire farm. Just the same, he shakes his head when he recalls how he used to farm.

“We were very conventional,” Snavely says. “You would just see the fields bare until spring, raw earth turned up that washed into the ditches. I can’t imagine getting a plow out of the barn now.”

After seeing productivity increase by leaving soil unplowed – what’s called no-till farming – Snavely got interested in cover crops eight years ago. With 1400 total acres, he now commits two-thirds to cover crops. Along with harvesting soybeans, corn and wheat each fall, he plants the same fields – sometimes while the main crops are still growing– with radishes, oats, legumes, cereal rye and clover in a rotation that locks in nutrients and holds them in the soil until spring. As a bonus, he injects much of his land with manure from his hog operation before putting on the cover.

“You just got to think deeper.” Snavely adds. “You can’t raise a crop without good soil. Organic matter breaking down helps improve the microbial activity and the air and water movement.”

According to Diesch, it costs about $3000 in seed and diesel to plant 100 acres of cover crops. Economic returns aren’t always immediate – as little as a 2-5% yield increase the first few years – but farmers like Dennis Reer on the other side of the county are still enthusiastic. His farm is 100% cover crops, and it has been since he acquired his land over 20 years ago. He says cover crops are nothing new.

“We grew up raising clover on all the wheat stubble,” Reer muses, wading through 120 acres of tender green flax he planted in September after harvesting soybeans. “It was kind of a rule of thumb back in the 80s. Most anybody that raised wheat, raised clover. Clover has a massive root system that really makes the soil mellow and loose.”

Reer has also embraced other innovations to improve his land. Where woodlands form a border to his north, he has protected the adjacent creek from runoff with wide margins of grass called filter strips. Amid the grass, an earthen bridge across a culvert pipe gives him access to his back acres.

At the end of the day, we climb a grain bin for a birds-eye-view, admiring the last rays of sunlight wash across a green carpet of flax and winter wheat rimmed by autumn-tinted woodlands.

Farming it forward

The next day, before leaving Seneca County, I catch a USDA training session hosted by Diesch’s agency at the farm of Bret Margraf, a champion of cover crop farming. In Margraf’s large equipment shed, 30 field agents from across Ohio gather around a table of open-bottomed soil trays with glass jars hanging below to catch water.

Two of the trays contain thick cover crops, a third has corn stubble and the other two are simply bare soil, devoid of plants. The speaker presses several dimes heads-up on the two bare samples and turns on an overhead sprinkler that sweeps back and forth, dousing all trays in one inch of “rain.” After five minutes, the dimes sit on islands of dirt with soil washed out around them. Muddy water is pouring into the glass jars hanging below, but the cover crop bottles are clear.

The speaker explains that erosion like this across 100 acres – just a dime thick – translates to hauling off 35 large dump trucks of farmland. Jaws drop. He takes one of the muddy-looking trays of bare earth and dumps it on the floor, revealing bone-dry dirt inside. Lacking roots and structure, the soil couldn’t absorb any water and the “rain” just washed away topsoil.

“My only regret is that we didn’t start cover crops 40 years ago instead of eighteen,” says Margraf afterwards. He first learned about cover crops when he went to Seneca Conservation for help battling erosion that was carving deep gullies into his sloped farmland. He was already no-till farming, but the ravines kept washing away. He learned that cover crops aren’t just about soil nutrients, they’re also about structure. He patched the ravines, planted cover crops on top, and was ready when hurricane remnants slammed the region several years later.

“It just saturated everything around here,” he recalls, “but we managed to shell [harvest] all of our corn that year without making a track. Every single neighbor cut ruts from one end of the field to the other and they were leveling all next spring before they could plant soybeans. It’s easy to put economics to it.”

Great Lakes future

With the success Diesch has had in Seneca County, the Great Lakes Protection Fund team is now exporting expertise like hers across the Great Lakes region with conservation organization training sessions.

“It’s a cultural change to get farmers thinking about what we’re leaving the next generation, not just the dollars and cents that get us through the year,” says Diesch. “We show that there are people who care about Great Lakes water quality in 20 years and that we as farmers can care too.”

Story and photos by Randall Hyman.

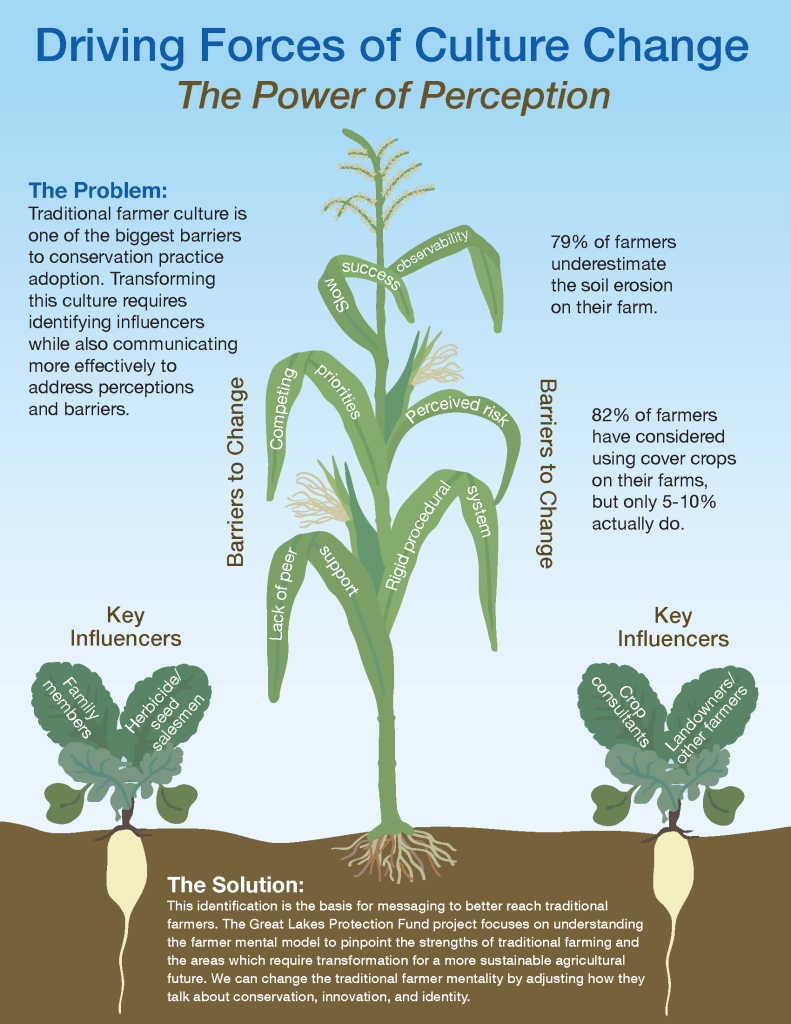

Infographic by Strategies to Engage Middle Adopter Farmers on Cover Crops team, supported by GLPF.